The brain and mind are not the same...

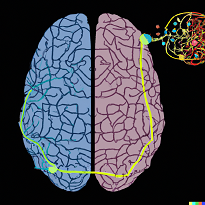

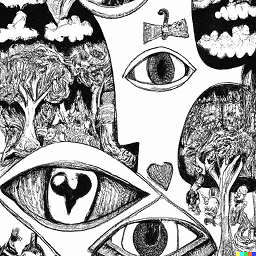

Like explorers venturing into uncharted seas, neuroscience has endeavored to map

the 10s of millions of connections in our brains. Some believe

that the key to unlocking the mysteries of the mind is in mapping these connections and great advancements in connectomics – the field of neuroscience that creates maps –

has produced neural maps of worms, flies, mice, and even parts of the human brain.

However,

philosophy has, throughout the course of human civilization, proposed that the mind is something

more than the connections in the brain. Something intangible. Something that perhaps cannot be

mapped in the same way. The thoughts, ideas, concepts, sensations, emotions, intuitions, and

imaginations that we conceive of as the mind exist somewhere in a space between. A space that

remains unquantifiable by even the most high-fidelity map of every neuron and every

connection in the human brain. Science, for all its’ ability to explain

complex phenomena, may be unable to explain the intricacies of our minds.

However,

philosophy has, throughout the course of human civilization, proposed that the mind is something

more than the connections in the brain. Something intangible. Something that perhaps cannot be

mapped in the same way. The thoughts, ideas, concepts, sensations, emotions, intuitions, and

imaginations that we conceive of as the mind exist somewhere in a space between. A space that

remains unquantifiable by even the most high-fidelity map of every neuron and every

connection in the human brain. Science, for all its’ ability to explain

complex phenomena, may be unable to explain the intricacies of our minds.

Explorers of a different kind venture inward into the vast oceans of our mind in search of the same elusive questions that have sparked curiosity for millennia.

Unpacking the black box...

The contents of the mind have been referred to as a “black box” of the unknown.

First conceptualized by American psychologist and behavioralist B.F. Skinner,

the box describes that which traditional behavioralists believe to be unobservable.

Skinner believed that what we perceive of as free will is actually an illusion created

by repeated reinforcement of responses to stimulus. To behavioralists like Skinner,

the mind exists as a black box – we know how it functions and can alter the outputs

(response) by altering the inputs (stimulus). Others argue that this is not the entire story.

That consciousness is more nuanced, and that the black box can be opened. Free will is deeper

than stimulus and response, and that the perception of having free will is enough to confirm

its existence. Opening Skinner’s “black box” requires reviewing all the contents between stimulus

and response to reconstruct the oneness of the mind.

The contents of the mind have been referred to as a “black box” of the unknown.

First conceptualized by American psychologist and behavioralist B.F. Skinner,

the box describes that which traditional behavioralists believe to be unobservable.

Skinner believed that what we perceive of as free will is actually an illusion created

by repeated reinforcement of responses to stimulus. To behavioralists like Skinner,

the mind exists as a black box – we know how it functions and can alter the outputs

(response) by altering the inputs (stimulus). Others argue that this is not the entire story.

That consciousness is more nuanced, and that the black box can be opened. Free will is deeper

than stimulus and response, and that the perception of having free will is enough to confirm

its existence. Opening Skinner’s “black box” requires reviewing all the contents between stimulus

and response to reconstruct the oneness of the mind.

We have mastered our understanding and organization of the external world through science, however, we have yet to master to the same degree our understanding and organization of the experience of the internal world through philosophy.

The

Continents of the Mind

Annika Anderson, Luke Chamberlain,

Randi Selvey

Based on the work of Dr. Logan Edwards, UW-Whitewater

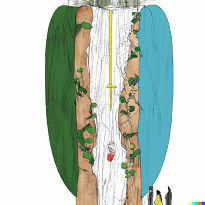

Much like early attempts by explorers to chart previously unexplored lands, this map is rudimentary

and far from complete.

A first blurry-eyed sketch with eyes not yet fully opened...

Body

We begin our journey through the continents at the mental conception of the body.

Mahatma Gandhi, known for his philosophies of non-violence, viewed the physical

body as a representation of violence, and that the presence of the body prevented humans

from practicing perfect non-violence. Gandhi was concerned with the idea of absolute

violence, or the injuring or killing of another living being. The requirements to

maintain the human body (food, water, shelter being the foundation of Maslow’s

hierarchy of needs) made violence, in Gandhi’s eyes, unavoidable.

The body continent is divided into four regions the empirical, the anatomical,

the experiential,

and the instinctual conceptions of the body.

We begin our journey through the continents at the mental conception of the body.

Mahatma Gandhi, known for his philosophies of non-violence, viewed the physical

body as a representation of violence, and that the presence of the body prevented humans

from practicing perfect non-violence. Gandhi was concerned with the idea of absolute

violence, or the injuring or killing of another living being. The requirements to

maintain the human body (food, water, shelter being the foundation of Maslow’s

hierarchy of needs) made violence, in Gandhi’s eyes, unavoidable.

The body continent is divided into four regions the empirical, the anatomical,

the experiential,

and the instinctual conceptions of the body.

Conscious Mind

Jean Paul Sartre, in his 1943 text Being and Nothingness, built upon Descartes’ ideas.

Consciousness

(or being) can be thought of as consisting of two types: being-in-itself (left) and

being-for-itself

(right). Being-in-itself concerns the being – or existence - of objects. In Sartre’s

mind,

this type of being was not the place of humans but rather objects. A person working as a server is

not

primarily a server (being-in-itself), rather a person is primarily a person

(being-for-itself) who

just

happens to be performing the function of a server.

Jean Paul Sartre, in his 1943 text Being and Nothingness, built upon Descartes’ ideas.

Consciousness

(or being) can be thought of as consisting of two types: being-in-itself (left) and

being-for-itself

(right). Being-in-itself concerns the being – or existence - of objects. In Sartre’s

mind,

this type of being was not the place of humans but rather objects. A person working as a server is

not

primarily a server (being-in-itself), rather a person is primarily a person

(being-for-itself) who

just

happens to be performing the function of a server.

Another way to think of being-for-itself is the idea of you as a person. Sartre said that to act in good faith, an individual must be aware of their own consciousness through self-reflection. They must not only be aware of themself, but also aware of their own self-reflection.

Subjectivity

How can two people have radically different experiences of the same event?

Two people walking together as a rainstorm starts have wildly different reactions – one

depressed, while the other elated. Subjectivity is the idea that one objective reality

(a rainstorm) can produce multiple interpretations due to differences in perception,

mood, feelings, abilities, creativity, language etc. gathered from previous experience.

How can two people have radically different experiences of the same event?

Two people walking together as a rainstorm starts have wildly different reactions – one

depressed, while the other elated. Subjectivity is the idea that one objective reality

(a rainstorm) can produce multiple interpretations due to differences in perception,

mood, feelings, abilities, creativity, language etc. gathered from previous experience.

The subjectivity of the self can be conceptualized as "me as a person" and "I as myself". In Buddhism, the self is thought of as only an illusion to be deconstructed. Paradoxically, the nature of the self can only be known through the “inquiring spirit” that seeks to doubt and negate the self.

As Danish philosopher Soren Kierkegaard famously said; “subjectivity is truth.”

Ego

The ego moderates the unrealistic id and the external world to govern how one ought to act in the

world.

The left region of the Ego continent is concerned with the ego for itself, or the selfish

ego.

Sigmund Freud’s pleasure principle, the foundation of psychological egoism, suggests that all

behavior

is motivated by self-interest seeking to maximize pleasure and minimize displeasure. Behaving in

this way,

however, is untenable and must be balanced by the ego within itself, the altruistic ego.

Debate

persists

to whether true altruism is possible if the performer of the act receives a reward in the form of

self-gratification for performing a good deed.

The ego moderates the unrealistic id and the external world to govern how one ought to act in the

world.

The left region of the Ego continent is concerned with the ego for itself, or the selfish

ego.

Sigmund Freud’s pleasure principle, the foundation of psychological egoism, suggests that all

behavior

is motivated by self-interest seeking to maximize pleasure and minimize displeasure. Behaving in

this way,

however, is untenable and must be balanced by the ego within itself, the altruistic ego.

Debate

persists

to whether true altruism is possible if the performer of the act receives a reward in the form of

self-gratification for performing a good deed.

Anti-Ego

Atop Maslow’s hierarchy of needs is the ideal self, self-actualization, or the ideal ego. Only when all other base needs (physiological, safety, love & belongingness, and esteem) have been met, can one be free to pursue one’s unique potential and fulfillment.

The conscience – Freud’s superego – is the inner voice that tells us when we’ve done

something wrong. It is the foil to the id and is learned from the outside world (parents)

at an early age.

The divine individual is the way in which some western philosophies beginning in ancient Greece

has

conceptualized

the soul. It is something that a person can risk and lose and that, after death, endures as a shade

in the

underworld. By contrast the eternal soul in many eastern philosophies purports that the human

soul is a

part of the soul of God and that we are part of an interconnected collective soul.

The conscience – Freud’s superego – is the inner voice that tells us when we’ve done

something wrong. It is the foil to the id and is learned from the outside world (parents)

at an early age.

The divine individual is the way in which some western philosophies beginning in ancient Greece

has

conceptualized

the soul. It is something that a person can risk and lose and that, after death, endures as a shade

in the

underworld. By contrast the eternal soul in many eastern philosophies purports that the human

soul is a

part of the soul of God and that we are part of an interconnected collective soul.

Others

The opposite of the self is the other. If the self exists, then the other exists as well.

The environment in which the self exists is the other that is in constant interaction with the self.

Materialism is the idea that all things develop as a product of their environment, and that change

occurs

when contradictions exist in the conditions of the environment (e.g., organisms evolve when there is

a

contradiction between their adaptive characteristics and their environment). The interaction between

the

self and the other can be conceptualized as others in me (right) and me in

others (left).

The opposite of the self is the other. If the self exists, then the other exists as well.

The environment in which the self exists is the other that is in constant interaction with the self.

Materialism is the idea that all things develop as a product of their environment, and that change

occurs

when contradictions exist in the conditions of the environment (e.g., organisms evolve when there is

a

contradiction between their adaptive characteristics and their environment). The interaction between

the

self and the other can be conceptualized as others in me (right) and me in

others (left).

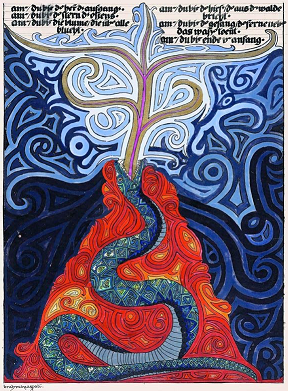

Will

19th century German philosopher Arthur Schopenhauer in his work The World as Will and

Representation

coined the term wille zum leben (the will to life), a force within all of us more powerful

than reason,

logic, or emotion. This is a mindless, aimless impulse that serves as the bedrock for all our

instincts

and the foundation of all life. Schopenhauer presents this as the driving force behind why much of

our social lives are

dictated to such an extent by romance and love.

19th century German philosopher Arthur Schopenhauer in his work The World as Will and

Representation

coined the term wille zum leben (the will to life), a force within all of us more powerful

than reason,

logic, or emotion. This is a mindless, aimless impulse that serves as the bedrock for all our

instincts

and the foundation of all life. Schopenhauer presents this as the driving force behind why much of

our social lives are

dictated to such an extent by romance and love.

The continent is divided into three parts. The collective will exists through social conditioning, norms, etc. and sits below the anti-ego’s will (right) and the ego’s will (left). The anti-ego’s will is dictated by morality, and the ego’s by reality.

Freedom

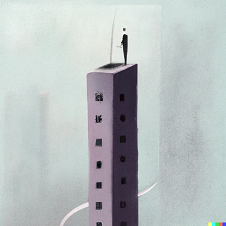

There are two regions in the Freedom continent: authoritative freedom (i.e., freedom of

thought and feeling),

and transformative freedom (i.e., freedom of action and creation). Kierkegaard considers a

man standing

on the edge of a tall building. The man looks over the edge and is overcome by two fears

simultaneously – the fear

of falling, and the fear of having a sudden impulse to jump. The second fear comes from the man

realizing that

he has the complete freedom to choose. Kierkegaard calls this the “dizziness of freedom,” and

suggests that we

experience it whenever we make a moral decision. Rather than becoming overcome by this anxiety, we

can instead

use it to enhance our self-determination and the sense of responsibility and ownership we feel over

the decisions

we make.

There are two regions in the Freedom continent: authoritative freedom (i.e., freedom of

thought and feeling),

and transformative freedom (i.e., freedom of action and creation). Kierkegaard considers a

man standing

on the edge of a tall building. The man looks over the edge and is overcome by two fears

simultaneously – the fear

of falling, and the fear of having a sudden impulse to jump. The second fear comes from the man

realizing that

he has the complete freedom to choose. Kierkegaard calls this the “dizziness of freedom,” and

suggests that we

experience it whenever we make a moral decision. Rather than becoming overcome by this anxiety, we

can instead

use it to enhance our self-determination and the sense of responsibility and ownership we feel over

the decisions

we make.

Unconscious Mind

When a smell or an image unexpectedly conjures up an old memory you had thought was long forgotten,

your mind is delving into the unconscious - the place containing the memories and impulses of which

in our day-to-day lives we are unaware. The collective unconscious is a concept introduced

by psychiatrist

Carl Jung that represents a form of the unconscious that is common to all humankind regardless of

culture.

Evidence for the existence of the collective unconscious is observable in people from opposite sides

of the world having dreams of imagery reminiscent of a shared mythology. This, Jung posits, suggests

that these images come from a shared origin in the mind.

When a smell or an image unexpectedly conjures up an old memory you had thought was long forgotten,

your mind is delving into the unconscious - the place containing the memories and impulses of which

in our day-to-day lives we are unaware. The collective unconscious is a concept introduced

by psychiatrist

Carl Jung that represents a form of the unconscious that is common to all humankind regardless of

culture.

Evidence for the existence of the collective unconscious is observable in people from opposite sides

of the world having dreams of imagery reminiscent of a shared mythology. This, Jung posits, suggests

that these images come from a shared origin in the mind.

Sitting above the collective unconscious are the unconscious body (left) and unconscious mind (right). According to Freud, there exists a vast unconscious mind below the conscious mental processes of which we are aware.

Objectivity

A debate as old as philosophy: nature (right) vs nurture (left). Does our environment make us what

we are (nurture), or

does our genetic blueprint define us (nature)? Nietzsche claims, somewhat paradoxically, that we are

both fated to be

as we are, and that we can create our own realization of ourselves. These seemingly contradictory

notions can be simultaneously

true. Our minds are formed by both the environment in which we are raised, and our genetic code.

A debate as old as philosophy: nature (right) vs nurture (left). Does our environment make us what

we are (nurture), or

does our genetic blueprint define us (nature)? Nietzsche claims, somewhat paradoxically, that we are

both fated to be

as we are, and that we can create our own realization of ourselves. These seemingly contradictory

notions can be simultaneously

true. Our minds are formed by both the environment in which we are raised, and our genetic code.

Consciousness exists, not in one place at one

time but across five planes corresponding to the five

colors on the map.

The Body

The Brain

The Mind

The Heart

The Soul

The Right Brain

The idea of brain lateralization – or the notion that different mental processes

are governed by different hemispheres of the brain – has become somewhat controversial.

There is a consensus however, that the right brain is associated with imagination, intuition,

art, and creativity…

The Left Brain

...the left with language, a sense of time, science, and logic…

One is not “left-brained” or “right-brained”...

As the mind wanders through the continents, patterns emerge.

what was first an unknown connection, becomes a well-worn route.

The continents of the mind rest at the conflux of two vast oceans…

Everything

nothingness.

nothingness.

nothingness.

nothingness.

nothingness.

nothingness.

nothingness.

nothingness.

nothingness.

nothingness.

nothingness.

nothingness.

nothingness.

nothingness.

nothingness.

nothingness.