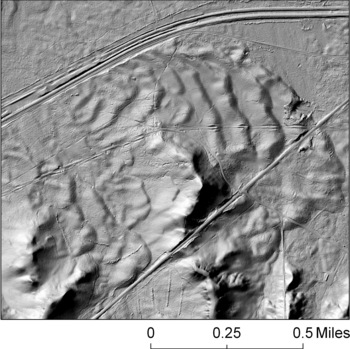

Newly created laser images of central Wisconsin show fields of dunes, most of which have never been seen before, that were blowing in the wind as recently as about 11,000 years ago.

“They have been hiding in plain sight,” says Joseph Mason, professor of geography at the University of Wisconsin-Madison. “Most are covered with trees and are only one or two meters high, so they are invisible from the ground.”

The precision instrument used to create the images, known as LiDAR, was flown for a very practical purpose: providing exact geographic data to county planners and engineers. Under ideal conditions, LiDAR – essentially a radar-like device that substitutes a laser for microwaves – can detect a height differential of just a few inches.

The dunes have now been sighted in Adams, Monroe, Columbia, Sauk and Juneau counties. (A few dunes in Adams County that are up to 40 feet high have previously been seen from the ground.) The dune sand blew in from the west, possibly from local river channels and eroded sandstone bedrock.

For a recent geography Ph.D. dissertation, Henry Loope dated the last movement of the dune sand using a technique that registers when grains of sand were last exposed to sunlight. Loope is now at the Indiana Geological Survey.

Having dates for moving dunes offers tantalizing clues to the past climate, Mason says, since grains of wet sand clump together and plants that grow in moist conditions block the wind and shelter the sand.

However, the situation may have been different just after the glaciers retreated and the climate was starting to warm, Mason says.

“The permafrost was melting, the soils were drier, and the vegetation did not have much time to grow and cover the dunes. Henry thinks that is when the sand was moving,” Mason says. It had to be dry for the sand to move on the wind, but it’s hard to say exactly how dry, so the message of these dunes about climate remains difficult to decipher.”

In his own studies, Mason has focused on loess – windblown dust – that gathered and became a key component of the highly productive silt loam soils of southern Wisconsin. “Silt loam holds moisture and fertility, and it does not have stones, so it’s ideal for agriculture,” Mason says.

“Loess can be one to two meters thick in Dane, Columbia and nearby counties, and its absence explains why the sand counties are the way they are,” he adds. “They tended to remain forested and weren’t agriculturally very productive before irrigation because they are covered with sand.”

The loess is most likely a combination of glacial silt blown from the Mississippi and dust from farther west, Mason says.

Mason, who is experimentally measuring how loess moves in Nebraska and China, thinks the dust rode Wisconsin’s central sands “like a conveyor belt. Dust constantly fell on the dunes, but it did not stay there; it got kicked back up into atmosphere.”

While the source of the loess is now better understood, Mason says he’s still surprised by the number of dunes that are suddenly visible in the sand counties. “Parts of Juneau County are completely covered with low dunes that you can’t see from the ground,” he says. “There are dunes in places like the Baraboo hills, where I never expected them.”

This year, public access to Wisconsin LiDAR data has become a lot easier thanks to the collaborative efforts of the Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources, the Geography Department’s Wisconsin State Cartographer’s Office, and WisconsinView at the UW-Madison’s Space Science & Engineering Center.