May 2, 2013 by Mary Ellen Gabriel, L&S News and Notes

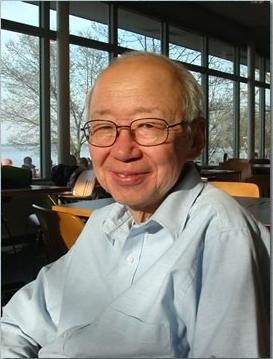

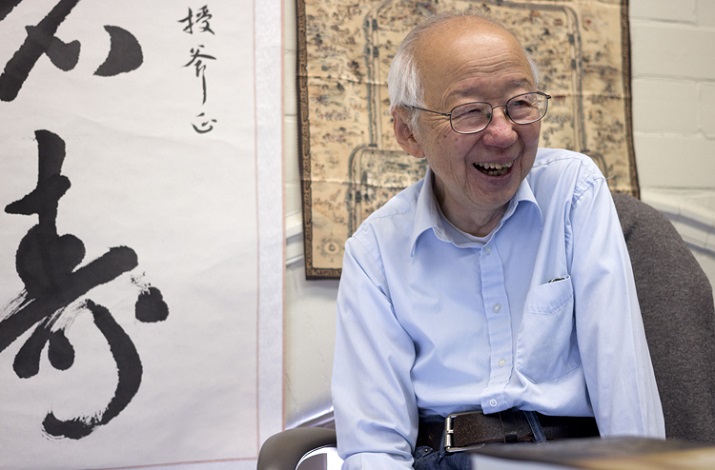

The State Street Starbucks belongs to Yi-Fu Tuan. He has a particular chair, a favorite table, and a habit of sitting with a book amid the busy clangor. Why is he so attached to this noisy place?“It’s my listening post,” says the 82-year-old emeritus professor of geography, who sits close enough, as he puts it, to “eavesdrop” on undergraduates studying calculus or history. “This phenomenon of young humans trying to find an answer may be unique in the whole universe,” he says. “That is what I enjoy about Starbucks.”The ways in which humans encounter and inhabit physical spaces, forming associations, impressions, loyalties, and aversions — all the while becoming more fully themselves — has fascinated Tuan for decades. Known as the ‘father’ of humanist geography, Yi-Fu Tuan taught at the University of Wisconsin-Madison from 1983 until his retirement in 1998 and remains an emphatic presence on campus. Through his books, essays, letters to colleagues, and innumerable conversations with students, Tuan has profoundly influenced the way scholars think about the relationship between people and their environments.In Oct. 2012, Tuan was awarded the Vautrin-Lud International Geography Prize, the highest honor a geographer can receive. In April, he received the inaugural AAG Stanley Brunn Award for Creativity in Geography, created to recognize “originality, creativity, and significant intellectual breakthroughs in geography.”On May 3, an interview with Tuan will be broadcast via the BBC program, “The Why Factor.”

“People think that geography is about capitals, land forms, and so on. But it is also about place — its emotional tone, social meaning, and generative potential.” — Yi-Fu Tuan, Professor Emeritus of Geography

In his wire-frame glasses and cardigan, Tuan is a slight figure threading the hordes on State Street on his way to the office he still keeps in Science Hall. But in the field of geography, he wields gigantic influence.“He’s viewed in geography departments around the world as someone who can shed light on how people form associations with the territory in which they reside, work, grow up, and grow old,” says Kris Olds, Chair of the Geography Department.

It was Tuan who gave rise to the recognition among geographers that the intimacies of personal encounters with space produce “a sense of place.”

“People think that geography is about capitals, land forms, and so on,” says Tuan. “But it is also about place — its emotional tone, social meaning, and generative potential.”

Humanist geography, a movement within the field of human geography (itself a sub-field of geography) arose in the 1970s as a way to counter what humanists saw as a tendency to treat places as mere sites or locations. Instead, a humanist geographer would argue, the places we inhabit have as many personalities as those whose lives have intersected with them. And the stories we tell about places often say as much about who we are, as about where our feet are planted.

Time, age, sadness, loss, goodness, happiness, and the concept of home are all themes Tuan has explored at length in his more than 20 books, including his best known work, “Space & Place,” and his most recent book, “Humanist Geography: An Individual’s Search for Meaning.” The upcoming BBC interview focuses on the book that might seem the least related to geography: “Dominance and Affection: The Making of Pets.” But that isn’t so, says Tuan.

“Geographers explore the power humans wield in nature — changing woods to make farms — for economic gain,” says Tuan. “But we also wield power for another purpose: play. Think about a fountain, made to leap for our pleasure. Dogs fetching a stick, elephants in the circus — even humans were sometimes turned into obedient animals. Thinking about the forces behind this power sometimes takes us to a darker realm.”

One of his most unique contributions may be his “Dear Colleague” letters, composed over decades and sent to colleagues and friends, relating observations and changes in his daily life against a backdrop of larger political, educational, and social change. Many of the letters appear in the volume “Dear Colleague;” the rest, more than 700, have been archived by Melanie McCalmont.

Tuan’s personal influence extends to legions of undergraduate and graduate students who have joined his seemingly limitless circle of friends over the years.

“Yi-Fu is one reason why I came to UW,” says Garrett Nelson, a Ph.D. candidate studying historical geography. “His influence looms large, and his door is essentially open all the time.”

As to why Tuan has remained so firmly rooted on campus 15 years after retirement, the answer is simply that it is home.

“The university imparts knowledge,” he says. “I feel at home in it, for to me home must nurture not only the body, and human bonds, but also the mind.”