By: Joel Gruley, Undergraduate Program Advisor, UW-Madison Geography

When you walk the third floor of Science Hall, you immediately notice the numerous striking maps displayed on the walls. These maps are the final student projects from GEOG 370, our introductory cartography class, and they draw people in, inviting exploration and admiration. I am one of these people – unable to traverse the third floor without lingering by the maps in awe. Recently, one map in particular caught my attention. Hand-drawn on large white poster board and rich in color, the map tells a compelling story about modern United States-Ethiopian relationships using demographic data, personal narratives, family photos, and Amharic script. I decided to learn more about it, and especially about the map’s creator given how evidently personal it is.

I reached out to Dr. Bill Gartner, who teaches GEOG 370. He explained that in this cornerstone assignment, students must tell a compelling story by applying the spatial data analysis and design skills they learn throughout the course to a topic of their choosing. Unsurprisingly, many students select a topic that is meaningful to them. “Whenever you’re making a map, it’s always very personal,” explains Dr. Gartner. To him, a map’s meaning is paramount, not necessarily its technical aspects. This resonated with Leah Bulbula, a senior Geography and Cartography/GIS double major, who took GEOG 370 with Dr. Gartner last year and produced the map I was drawn to on the third floor.

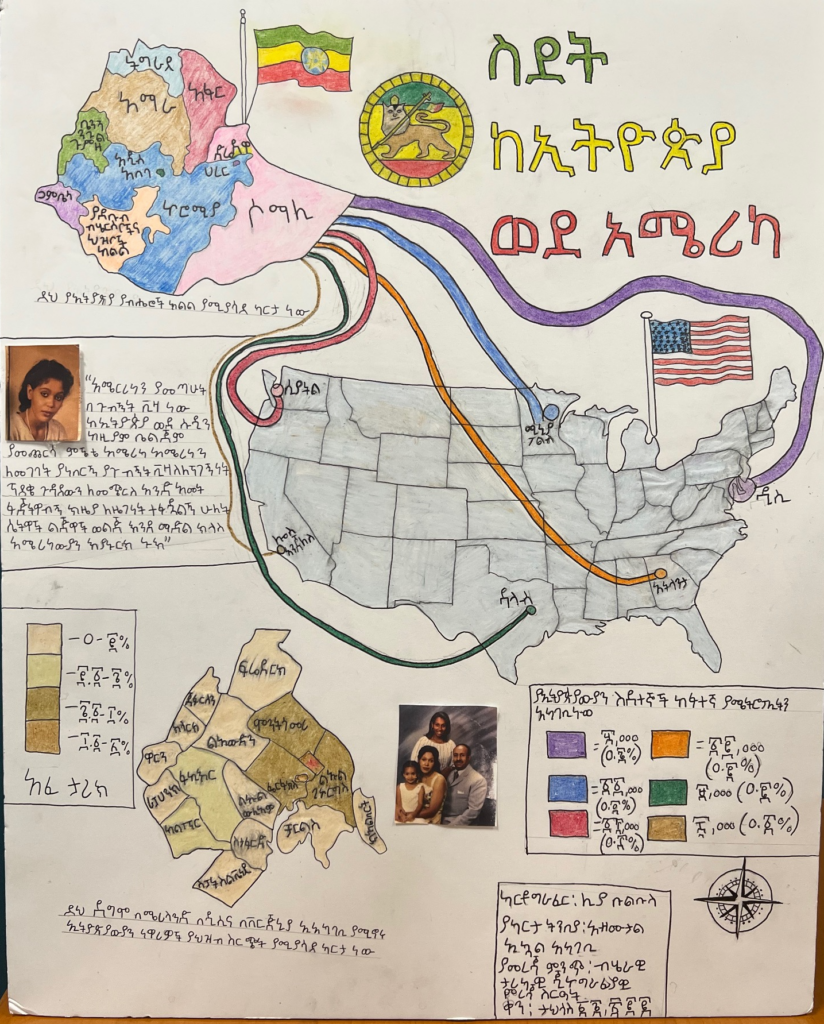

Entitled “Ethiopian Migration to the United States,” the seed for Leah’s map was planted when Dr. Gartner showed an endonym map of Africa during lecture. Upon seeing African place names written in local script, Leah, the daughter of Ethiopian immigrants, knew she wanted to map something related to Ethiopia, and to use Amharic – the official language of Ethiopia – script, which would help decolonize her map as well as beautify it. She eventually settled on mapping contemporary Ethiopian migration to the U.S. because the topic is so close to her and her family.

Leah uses a flow map to represent modern Ethiopian migration to the U.S. Lines of varying widths – the greater the width, the greater the number of emigrants – and colors “flow” from Ethiopia, its regional ethnic and linguistic diversity depicted, to six primary U.S. destinations. Dr. Gartner sees these lines as symbolizing an “umbilical cord”, intimately linking the two countries together. Seattle is one of the destinations – where Leah’s father, Firew Bulbula, arrived in 1972 at the age of 19 as he fled a political conflict in his home country. Leah’s father was the first of her family to arrive in the U.S.

Leah’s mother, Abiti Tilahun, arrived in 1986 in Washington, D.C., also at 19 years old. Fleeing violence in Ethiopia, she was granted political asylum and eventually became a U.S. citizen. A photo of Ms. Tilahun, taken around the time she arrived, graces the map, as well as a quote from her in which she describes how challenging life in the U.S. was initially, but how, with the help of a growing and supportive Ethiopian community in the D.C. area, the U.S. eventually became her second home. Human migration maps often lack human context – Leah wanted to push against this by highlighting her mother’s story as it personalizes her map and provides crucial background for the Ethiopian experience in the U.S.

Leah also included a choropleth map – which uses differences in color to indicate differences in values – inset to show the current Ethiopian population in the D.C. area, boasting the largest Ethiopian population in the world outside of Ethiopia itself, where she grew up and her parents co-founded a church to serve the thriving Ethiopian community. Accompanying this inset is a picture of Leah’s family, dressed in formal clothing, taken when she was just three years old. Leah included this photo as a visual testament to how much her parents had accomplished in the U.S. despite the myriad challenges and hardships they faced, a feat of which she is immensely proud.

Maps can be many things. Leah’s map is informative and beautiful, and all the more powerful given her skillful use of personal narratives, family photos, and endonyms. Her decision to make the map painstakingly by hand, further personalizes it. Leah ultimately made this map for her family, and the process helped her reflect on her parents’ remarkable journey as well as the journey of other Ethiopian-Americans. It also helped her realize how fortunate she is to be a part of the larger Ethiopian-American community. Maps, as Leah’s example demonstrates, often radiate personal meaning. Next time you are in Science Hall, take some time to gaze at the student maps displayed on the third floor, all full of personal meaning.