From UW-Madison News: October 24, 2022

By Abigail Becker

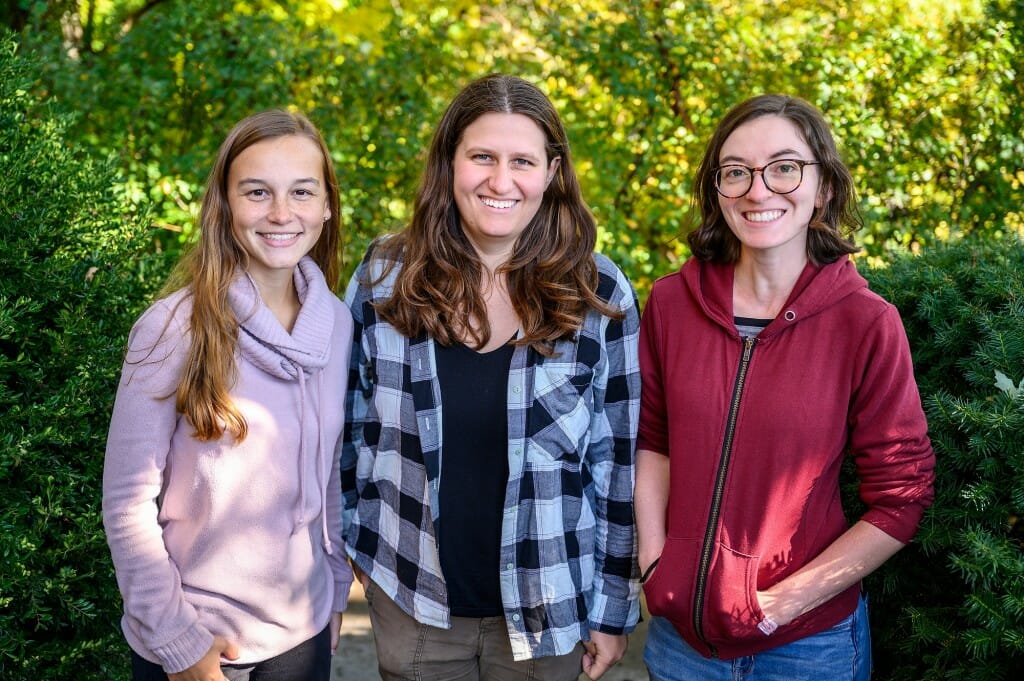

From left to right, graduate students Sara Pabich, Elizabeth Berg, and Becky Rose are collecting data for a new heat warning system that could help save lives. Photo: Althea Dotzour

As dangerous heat levels are breaking records across the United States and the world, three University of Wisconsin–Madison graduate students are collecting data to inform a heat warning system based on health outcomes — a tool they hope could eventually save lives.

Nelson Institute Environment & Resources PhD students Elizabeth Berg and Becky Rose and Public Health and Public Affairs masters degree student Sara Pabich are tracking extreme heat events in six cities, including Madison and Milwaukee.

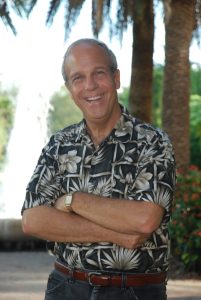

They’re working with climatologist Larry Kalkstein as a part of the Wisconsin Heat Health Network, which is supported by UniverCity Alliance and collaborators that include the City of Madison, Milwaukee County, City of Milwaukee, and Dane County. Their research will inform a warning system in Madison and Milwaukee based on health outcomes that considers mortality and weather data rather than only meteorology.

“People’s response to heat is more important than the intensity of the heat itself. We are trying to determine when people are most sensitive to heat waves,” said Kalkstein, who is the president of Applied Climatologists, Inc. and chief heat science advisor for the Adrienne Arsht-Rockefeller Foundation Resilience Center. “Health practitioners want to know when people are most vulnerable to heat related illnesses and deaths.”

The stakes are high. According to a 2021 report from the Wisconsin Initiative on Climate Change Impacts, the number of days that will exceed 90 degrees in Wisconsin is expected to triple by mid-century. Extreme heat already causes more fatalities than any other weather-related event in the state and the country.

“The most direct hopeful outcome will be saving people’s lives during these heat events that will become more and more frequent and severe,” said Rose, who is advised by Nelson Institute associate professors Aslıgül Göçmen and Annemarie Schneider.

In practice, the new warning system could help policymakers make decisions for how their population can stay healthy during extreme heat. This could include neighbors deciding to check in on an elderly resident and a city opening more cooling centers throughout a community affected by extreme heat.

Berg works in the Department of Agronomy and Nelson Institute Center for Sustainability and the Global Environment (SAGE) affiliate, Chris Kucharik’s lab. She has been working with Kalkstein for more than two years and said it’s important for leaders to consider the locations and demographics of those who are being affected disproportionately by the heat.

In Milwaukee, Berg is analyzing more specific health data by zip code instead of the entire city.

“We’ve already known that extreme heat doesn’t impact everyone equally,” said Berg, noting that factors like housing and socioeconomic status are contributing factors. “I’d love for this to be a starting point for not just increasing communication about heat, but to make it easier for cities to target interventions specifically where they’re needed.”

Madison and Milwaukee became involved in 2020 when UCA Managing Director Gavin Luter organized a group of interested stakeholders to have an initial networking meeting about heat and health. This group included Dane County, the City of Madison, the Sustainable Madison Committee, the Wisconsin Initiative on Climate Change Impacts, and UW–Madison’s Global Health Institute.

Eventually, the group became the Heat Health Network and expanded to include representatives from the Wisconsin Department of Health Services, Milwaukee County’s Office of Emergency Management, the City of Milwaukee Sustainability Office, the Milwaukee Metropolitan Sewerage District, UW–Madison’s agronomy department, a University of Minnesota-Twin Cities graduate student, and Public Health Madison & Dane County.

Pilot program at work

These collaborators are coordinating with the National Weather Service’s Sullivan office this summer to evaluate the pilot program. They hope the lessons learned in Madison and Milwaukee will support exploring the feasibility of expanding the heat health warning system around the state.

“The whole purpose of this at the end of the summer is to compare all of the data to see how closely it follows the National Weather Service’s heat advisories,” Pabich said. “We want this system to be effective and replicable to other at-risk areas in the state. Essentially, we want it to align with the National Weather Service but also add the human mortality rate component.”

Kalkstein’s algorithm factors in historical health data, historical air mass types and frequency of each type, and calculated heat wave intensity, to produce one of three heat wave categories that increase numerically by risk.

The data collection site has been running since mid-May and has been adjusted to warn stakeholders and meteorologists when a city is in the top 5% of excessive heat conditions. The student researchers track the data daily, comparing how the algorithm’s heat warnings align with warnings from the National Weather Service.

This work is financially supported through the Climate-Ready States and Cities Initiative through the Centers for Disease Control that was secured by DHS.

The Adrienne Arsht-Rockefeller Foundation Resilience Center, which aims to build individual and community climate resilience in the wake of climate change, is funding separate but related work to implement a heat ranking system. Other cities currently being studied include Los Angeles; Miami; Kansas City, Mo.; Seville, Spain; and Athens, Greece.

This summer marked a milestone for Seville, which became the first city in the world to implement the ranking program. The city also named its first heat wave Zoe.

“I’m just glad to have a system that is based on health outcomes and not strictly on meteorology,” Kalkstein said. “It’s very important to have that because most of the stakeholders respond to emergency room visits, mortality — all of these things that are really important when it comes to heat waves.”

Cities across the nation and world are taking notice. Kalkstein said he’s fielded inquiries from New Orleans, South Korea, and Brazil and “wouldn’t be surprised” if about a dozen more cities joined next year.

What’s next?

In Madison and Milwaukee, the next step is to evaluate.

Kalkstein said a summer’s worth of data will inform if the algorithm should be adjusted. He also suggested forming a heat taskforce to discuss and coordinate what policies the cities are implementing when a heat warning is called.

This is important because if the ranking system is implemented, municipalities would need to make sure residents understand it and what resources they can use to stay cool, safe, and healthy.

After observing the data for about two months, Berg said she can confirm that extreme heat is more dangerous in areas with more temperate and less consistently warm climates, like Madison.

“In the U.S., it’s been the places that have much more seasonal variation where we have met those metrics for dangerous heat waves,” Berg said.

Pabich, who is also a climate data assistant with Dane County, is looking forward to discussing the public education component of implementing a new ranking system.

“I really love the public health angle of combining how the environment affects public health and what we are doing both at the county level and then what the Wisconsin Department of Health Services is eventually going to do with this information,” she said.

Rose said she hopes the Wisconsin Heat Health Network’s work will result in meaningful policy changes not only like opening cooling centers, but implementing protections for workers whose jobs keep them outside.

“Everything is connected,” Rose said. “Health is a part of the picture, but it’s also tightly bound with economic wellbeing and social wellbeing.”