Below, project director Matthew Edney describes triangulation, one of the technical aspects of topographical mapping. Learn more about how the science of cartography spread during the nineteenth century in our newsletter and other essays at 2025 Outreach Extras.

Please consider contributing your support to the international effort that is the History of Cartography Project – click “Make A Gift” at right to donate online!

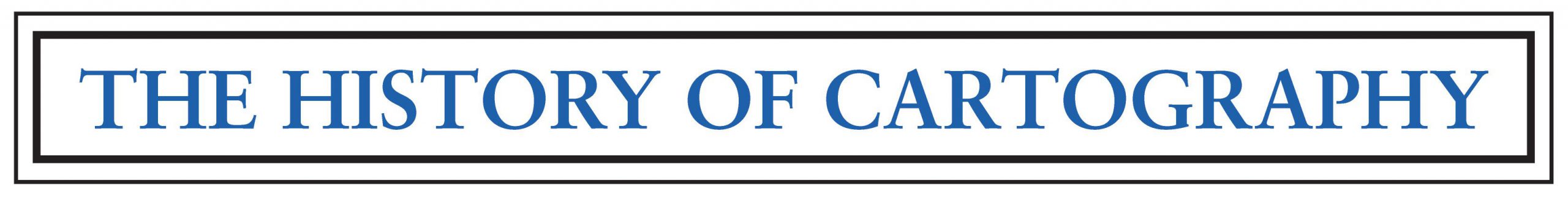

Figure A. Triangulation over an imagined landscape, from Jørgen Henrik Rawert, Forelæsninger over den geometriske trigonometriske og militaire landmaaling tilligemed nivelleringen (Copenhagen: Sebastian Popp, 1793), pl. XVII.

This is fig. 885 in Michael Jones, “Topographical Mapping in Nordic Countries,” in Volume 5.

Hand-colored copper engraving, 23.5 × 20 cm.

Image courtesy of Det Kgl. Bibliotek; The Royal Danish Library, Copenhagen (DA 1.–2.S 18 4º).

Triangulation

Triangulation is the method of defining triangles spread across a landscape by measuring the angles between imaginary lines running from height to height, whether tall buildings or high hills (fig. A). The lines are chosen so as to form roughly equilateral triangles, whether in a general mesh (as fig. A) or in long chains (as fig. 3 in the main essay National Topographical Surveys and “Cartography”). If one side of a triangle is very carefully measured—the baseline (fig. B)—then the sides of all the other triangles in the network can be calculated by trigonometry. Once C. F. Gauss developed the statistical method of “least squares” to manage all the inevitable errors within a triangulation network (published 1809), surveyors also measured a second baseline, the base of verification. Comparison of the measured length of the second baseline against its length as computed through the network from the primary baseline allowed surveyors to quantify those errors and distribute them across the network. British engineers called this process, “trigonometrical surveying,” but eventually adopted the alternative, French term of “triangulation.”

Rigorous triangulations have two functions. Primary triangulations, featuring large triangles measured with great care, are used to measure the lengths of long arcs across the earth’s surface, which are key data for calculating the precise size and shape of the earth. The primary triangulation then serves as the foundation for secondary and perhaps also tertiary triangulations, each featuring smaller triangles; the lesser triangulations can be measured with less care (and cost) because the primary triangulation constrains their observational errors. The result is a dense array of accurately and precisely determined positions that in turn control detailed topographical or hydrographic surveys. Grounded from the start in an overarching, hierarchical triangulation, all of the detailed surveys are easily fitted together into a single, multisheet map of the country.

MHE

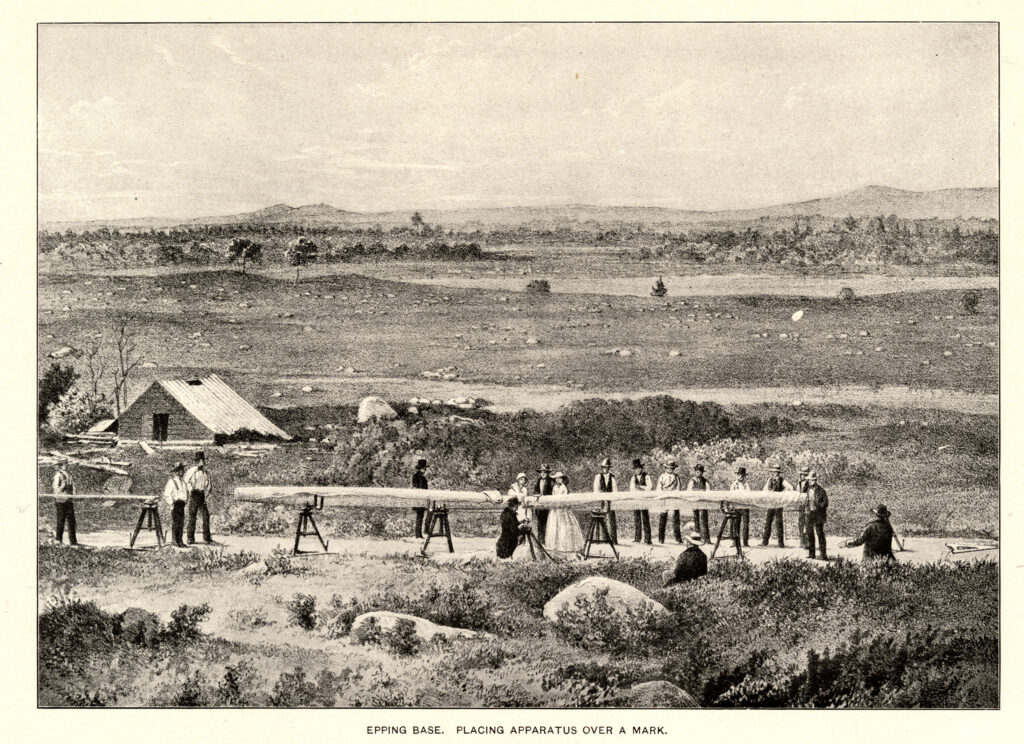

This is fig. 333 in Cecilia A. Smith, “Geodetic Surveying in the United States,” in Volume 5.

Lithograph, 14 × 19 cm.