The Maps We Play…

An in-depth look at the topic of cartographic games that we highlighted in our 2020 outreach letter.

The History of Cartography Project relies on donations from friends like you. May we count on your support? Donate online in one step using the “Make a Gift” button on the right. Learn how your gift helps and find more ways to give using the “Support the Project” link above.

One of the many ways in which The History of Cartography differs from earlier histories of the subject is the presence within its pages of maps that were used as art and as a source of enjoyment.

Fig. 1. Portion of a fresco from the peristyle of the Villa of P. Fannius Synistor at Boscoreale, near Pompeii, ca. 50–40 BCE, showing a celestial globe-cum-sundial. Original (entire): 72 × 50 cm. Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York (Rogers Fund, 1903; Acc. 03.14.2). Click image to see in high resolution on the institutional website.

In Volume One, for example, we can see reproductions of frescos in ancient villas that depicted maps: the landscape views and plans dated to about 1,500 BCE, from the Aegean island of Thera, and a celestial globe drawn in perspective found near Pompeii and dated to about 50 BCE (fig. 1). We cannot say for certain how the people who lived and worked in these villas would have viewed these images on their walls, but we can say that one function they served was that of decoration: they pleased the eyes and mind.

Games and Diversions in the History of Cartography… and in The History of Cartography

Yet, even though a major theme in the study and appreciation of early maps has been their nature as works of human craft and graphic skill, such that they have often been displayed in homes and libraries not just as relics of the past but as beautiful relics of the past, scholars traditionally evaluated and assessed early maps only from the perspective of their scientific qualities. How well do they represent the earth’s surface, and do they represent it better than other early maps? Indeed, libraries rarely collected map games and other kinds of popular maps because they were deemed to be mere ephemera, so they can be hard to find today.

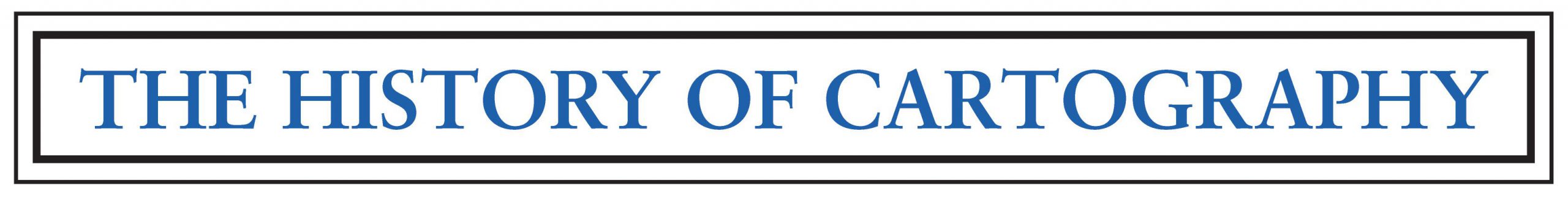

Fig. 2. Utagawa Hiroshige II (Shigenobu), Edo Meisho Ikken Sugoroku [Board Game of the Famous Places in Edo in One View] (Tokyo, 1859). Sugoroku was a game similar to snakes-and-ladders, popular in Japan in the nineteenth century. Original: 71.5 × 71 cm. Osher Map Library and Smith Center for Cartographic Education, University of Southern Maine (Osher Collection). Click image to see in high resolution on the institutional website.

The only problem with this expansion of cartography’s scholarly dimensions is that it has required much more to be written about early maps! This is why the volumes of the History have grown both in number and size, so that they could still examine the scientific and technical aspects of mapmaking in the past even as they embraced the cultural and social uses of early maps.

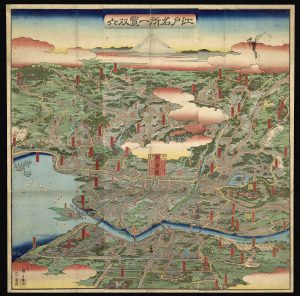

Fig. 3. Streamline Train Game: Exciting, Amusing, Educational (1936). Box cover for a game tied to the promotional tour of the “Million Dollar Rexall Streamlined Train.” Original: 37 × 52 cm. Osher Map Library and Smith Center for Cartographic Education, University of Southern Maine (Osher Collection). Click image to see in high resolution on the institutional website and to see the game board.

An important element of the new approach to map history has been to consider the large array of “popular maps.” These are maps made not for building things, nor for moving people, nor for communicating information about the world, but for a host of other reasons: to educate, to persuade, to amuse, to entertain, and to divert (fig. 3). The geographical simplification inherent in such maps mean that they were long dismissed by map historians as simple “curiosities.” Now, however, we understand map games and diversions as a major form of map use among children and adults alike.

The Basic Kinds of Map Games

Map games developed in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries in conjunction with the growth of the print trade and the expansion of both male and female literacy throughout the middling sort. The first form was the playing card (which of course has the same name as map in French, carte, and German, Karte). From Jill Shefrin’s entry, “Games, Cartographic,” in Volume Four, Cartography in the European Enlightenment, we learn that playing cards with map designs were first produced in the late sixteenth century and became popular in the seventeenth (fig. 4).

Fig. 4. Pierre du Val, Les tables de geographie, reduites en un jeu de cartes (Paris, 1669). Uncut sheet of fifty-two geographical playing cards, one continent per suit (hearts to Europe, diamonds to Asia, spades to Africa, and clubs to the Americas). The cards contain lists of countries and places, with medallions of ethnographic figures or persons for the face cards; four extra cards depict maps of the continents. Original: 42 × 54 cm. Norman B. Leventhal Map Center, Boston Public Library (GV1485 .D88 1669). Click image to see in high resolution on the institutional website.

Fig. 5. Geographisches-Lottospiel, ganz neue vermehrte u. verbesserte Auflage (ca. 1835–55). As the lengthy subtitle to this special game explains, by playing this geographical lotto, children would “easily get to know the main points of geography, the number of inhabitants of all countries in the world, all names of the capital and residences, the location of the same, [and] the names and birthdays of the rulers.” The game’s object, like bingo, was to fill the cells of the board (each a geographic location) by collecting relevant tiles or cards. Original: 17 × 24 cm. Norman B. Leventhal Map Center, Boston Public Library (GV1485 .G46 1855). Click image to see in high resolution on the institutional website.

Intended for passing time frivolously, or even immorally in the case of gambling, cartographic playing cards aimed to be “improving.” They included basic outlines of countries and regions accompanied by other text and graphics giving information about the regions depicted. Players could not help but learn some geography in the midst of their fun and family bonding (fig. 5). See also, for example, a card from a 1779 deck published in Florence or an 1845 set of cards of U.S. states designed to promote “geographical conversations.”

(Here’s a fun piece of trivia: in developing one of the first card catalogs, the librarians of the Revolutionary-era Bibliothèque nationale, formerly the Bibliothèque royale, wrote each entry on the blank versos of playing cards; because the cards were of standardized size and on stiff paper, they were much easier to handle and manage than the odd-sized slips of paper that librarians had used previously. I have no idea if any of those first cards survive, or if any have maps on their [former] rectos!

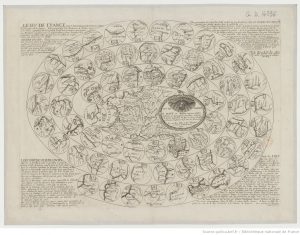

Fig. 6. Pierre du Val, Le Ieu de France (Paris, 1671). Bibliothèque nationale de France, département Cartes et plans (GE D-14836). Click image to see in high resolution on the institutional website.

The second kind of map game was the board game, which seem to have originated with the Parisian géographe du roi, Pierre du Val in the 1640s. Even as he published “proper” maps and atlases, du Val turned the spiral racetrack of the “game of the goose,” an adult (i.e., gambling) game, into an improving pastime for children. Each space along the track in his le jeu du monde (the game of the world) of 1645 bore a map of a country and perhaps other information for children to study as they awaited their next turn. You can see an image of this game in Volume 4, fig. 250, in Shefrin’s entry. The board-game format was rapidly adapted to particular countries, France first in du Val’s le jeu de France (fig. 6), where children pushed their counters across maps of provinces. For other map board games by du Val, see Le ieu de France pour les Dames; and Le jeu des princes souverains de l’Europe.

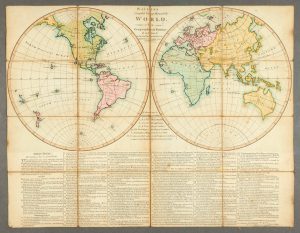

Fig. 7. John Wallis, Wallis’s Complete Voyage Round the World: A New Geographical Pastime (London, 1802). Players spun an eight-sided totem, numbered 1 to 8, to determine how many spaces to move along the route across the map. Players could be trapped, for example at Port Jackson (Sydney), site of the new British penal colony. This game is reproduced in Adrian Seville’s entry on “Games, Cartographic,” in Volume Five, Cartography in the Nineteenth Century. Original: 49 × 63 cm. Huntington Library, San Marino, Calif. (47211). Click image to see in high resolution on the institutional website.

Matthais Kirchoffer, SJ, took the perhaps logical step, in 1659, to suggest that the racecourse be drawn across an actual map to make his orbis lusus (game of the world). This kind of board game only grew very popular across Europe after 1750, perhaps reflecting the rise of the Grand Tour: players could sit at home and emulate the rich youths who travelled the continent to improve themselves. There was also a clear connection to European imperial activities around the world. Indeed, some British board games were made to look just like the kinds of maps that travelers might carry; they were dissected and the parts mounted onto a cloth for easy folding and unfolding (fig. 7). Players had to provide their own tokens and dice.

Fig. 8. Puzzle formed by pasting a map of North America from Jean Palairet’s Atlas méthodique (London 1755) onto a thin slice of mahogany and then slicing along boundary lines with a jigsaw. Palairet’s atlas featured simplified maps specifically intended to assist children’s learning (see Volume 4, fig. 82). This “homemade” puzzle is one of eight commissioned by Lady Charlotte Finch, governess of the children of George III, and housed in a puzzle cabinet (see Volume 4, fig. 251). Victoria & Albert Museum, London (B.1-2011). Click image to see in high resolution on the institutional website. To see all six surviving puzzles, see https://collections.vam.ac.uk/search/?q=Jean%20Palairet.

The third basic kind of map game was the puzzle, in which the map was cut into pieces that the child (or adult) had to reassemble (fig. 8). As early as 1727, Eberhard David Hauber suggested that governesses might cut a map along national boundaries to create such a puzzle. In the 1750s, Jeanne-Marie Leprince de Beaumont, a French governess in London, seems to have hit upon the idea of pasting maps to wood and then using a jigsaw to cut them up. The practice was commercialized by the London publisher John Spilsbury in the following decade. While expensive—the jigsaw puzzles sold for up to a guinea apiece (£1 1s, or about £126 in the present day)—they proved popular. Moreover, few of these early cartographic games survive, suggesting that they may have been well-used.

Mass Literacy, Mass Consumption, and the Proliferation of Cartographic Pastimes

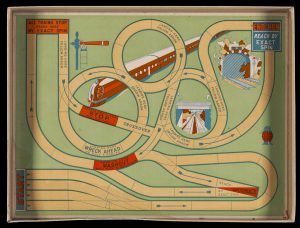

Fig. 9. Rocket (1937). An abstract track representing a complex high-speed train system. Original: 29 × 39 cm. Osher Map Library and Smith Center for Cartographic Education, University of Southern Maine (Osher Collection). Click image to see in high resolution on the institutional website.

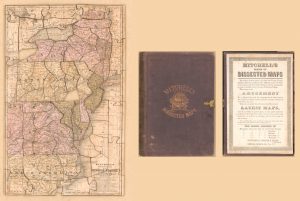

Fig. 10. S. Augustus Mitchell, Mitchell’s Dissected Map of the Middle States (Troy: Merriam, Moore., 1854). The Library of Congress has digitized many nineteenth-century map puzzles from its collections, some (like this one) incomplete. Sixty-four-piece jigsaw puzzle; paper on wood; 43 × 27 cm. Geography and Map Division, Library of Congress (G3791.A9 1854 .M5). Click image to see in high resolution on the institutional website.

The rise of mass education in the nineteenth century was matched by the dramatic reduction in the cost of printed goods as industrial technologies were applied to increase print runs to meet the ever-growing demand. In addition to textbooks and atlases for school children—recast in light of the realization that children were not just small adults but required educational materials adapted to their developing cognitive capacity—commercial publishers expanded their offerings of educational games and pastimes.

Seville explores some of their aspects in his entry for Volume Five. All three of the older forms of map game continued to be produced: cards, board games (whether spiral, abstract [fig. 9], or across maps), and puzzles (fig. 10). But as such games proliferated, they also began to specialize. A key theme in Seville’s entry is the way in which the games were organized in specifically geographical terms: the first known U.S.-produced board game (1822) featured a track over the eastern United States in which players were expected to correctly name the place where they had landed or lose a turn; an 1811 British set of playing cards lacked suit markers, and cards were played only if the county they depicted adjoined the county showed in the card lying face-up on the table.

Fig. 11a. Crossing the Ocean (New York: Parker Bros., 1893). (a) Cover, 23 × 38 cm. (b) Board, comprising an abstract depiction of the Atlantic. (c) Playing pieces. Osher Map Library and Smith Center for Cartographic Education, University of Southern Maine (Osher Collection). Click on images for more information.

By the 1870s, the introduction of relatively inexpensive color printing and the technical ability to integrate the mass production of several materials into a single commercial package together gave rise to the modern, self-contained board game: a box containing a board, pieces, dice or spinners, and rules (fig. 11). Many games featured world travel by steam ships and trains (and later, airplanes), and they used maps on their boards. A significant development in such games was the replacement of tracks with actual networks of roads (Stop Thief!, 1938) and railways (The Limited Mail and Express Game, 1894).

Fig. 11b. Crossing the Ocean (New York: Parker Bros., 1893). (a) Cover, 23 × 38 cm; (b) board, comprising an abstract depiction of the Atlantic; and (c) playing pieces. Osher Map Library and Smith Center for Cartographic Education, University of Southern Maine (Osher Collection). Click images to see in high resolution on the institutional website.

Fig. 11c. Crossing the Ocean (New York: Parker Bros., 1893). (a) Cover, 23 × 38 cm; (b) board, comprising an abstract depiction of the Atlantic; and (c) playing pieces. Osher Map Library and Smith Center for Cartographic Education, University of Southern Maine (Osher Collection). Click images to see in high resolution on the institutional website.

Fig. 12. Round the World with Nellie Bly (America, 1890). In this game, each space on the board is a day of Bly’s journey. Original: 41 × 22 cm. Osher Map Library and Smith Center for Cartographic Education, University of Southern Maine (Osher Collection). Click image to see in high resolution on the institutional website.

Such games were also tied in with popular novels and stories about travel. A French board game from 1875 sought to recreate Phileas Fogg’s race in Jules Verne’s Around the World in 80 Days (1872), and in 1890 there were games connected to the grand adventure of Nellie Bly (pseudonym for the journalist Elizabeth Cochrane, fig. 12) who traveled around the globe in less than 80 days! A different Nellie Bly game has been imaged by Yale University Libraries.

The inculcation of imperial sentiments among the young was a major theme of nineteenth- and twentieth-century puzzles and board games. The following images (figs. 13–15) are of just three of many works that present Westerners as the legitimate rulers of the world and that reduce the inherent cruelties of empire to mere games.

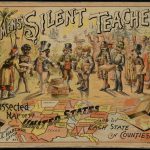

Fig. 13. Rev. E. J. Clemens, Clemens’ Silent Teacher: Dissected Map of the United States and of Each State in Counties (Clayville, N.Y., 1880s). This box contained a double-sided puzzle, with a map of Pennsylvania on one side and a map of the United States on the other. Original: 19 × 24 cm. Norman B. Leventhal Map Center, Boston Public Library (G3821.F7 1880 .C54x). Click image to see in high resolution on the institutional website.

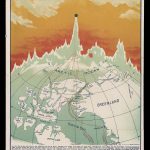

Fig. 14. North Pole Party: Pin the Flag to the Pole (Akron: Saalfield Publishing, 1909). A game based on the competing claims of Robert Peary and Frederick Cook to have both reached the North Pole first. Osher Map Library and Smith Center for Cartographic Education, University of Southern Maine (Osher Collection). Click image to see in high resolution on the institutional website.

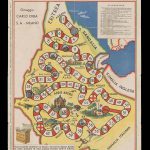

Fig. 15. La Conquista dell’Abissinia (n.p.: Carlo Erba, 1936). A game track intended to represent the Italian invasion of Abyssinia (1935–36), the last part of Africa uncolonized by the European powers. Original: 54 × 38 cm. Osher Map Library and Smith Center for Cartographic Education, University of Southern Maine (Osher Collection). Click image to see in high resolution on the institutional website.

Spatial Abstractions

A further development in the later nineteenth century was the alteration of jigsaw puzzles. They began to be made by cutting up the map in a pattern unrelated to the boundaries of the regions depicted. One such puzzle from 1880 was sliced up into a series of irregular, straight-edged trapezoids (fig. 16). In such puzzles, and especially highly complex modern jigsaws with hundreds if not thousands of pieces, the relationship between the shape of the individual pieces and geographical regions was completely lost. The goal of the puzzle is to manipulate the pieces by shape and color.

Fig. 16. Outline Map of the United States of America (Springfield: Milton Bradley, ca. 1880). Forty-eight-piece jigsaw puzzle. Osher Map Library and Smith Center for Cartographic Education, University of Southern Maine (Osher Collection). Click image to see in high resolution on the institutional website.

Fig. 17. A Dutch edition of Risk being played. By © Jorge Royan / http://www.royan.com.ar, CC BY-SA 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=50453387

The modern board game has further abstracted the space of countries and the world. The logic of the game has altered the logic of geographical space. One way in which this has happened is through the modification of regions to permit complex war games. These last are very much the product of post-World War II and the age of global war and are epitomized by the massively popular game, Risk, invented by Albert Lamorisse in 1957 and published by Parker Brothers (later Hasbro) in multiple editions around the world (fig. 17). To make the game work, Lamorisse had to create new regions that do not exactly match political regions of the real world, and it of course ignored actual geographical conditions. Greenland is as salubrious as India. However, Risk does demonstrate the ability of games to teach geography: I for one know Irkutsk from Yakutsk from playing the game, way back when!

The ability of motorized transport and especially air travel to move in any direction gave rise to the division of the game board into abstract grids and tessellations. This practice can be seen in the 1893 game Crossing the Ocean (fig. 11). The grid of squares and the hexagonal tessellation came to the fore in more recent games, whether on predefined boards, such as Settlers of Catan, or those created by game players themselves, as in Dungeons and Dragons.

As with maps generally, game maps have made the transition to the digital age. Indeed, maps and mapmaking are absolutely crucial to the wide variety of role-playing games—whether featuring conflict (e.g., Civilization), world building (e.g., Minecraft), and [and/or?] personal mayhem (e.g., Grand Theft Auto). There is even at least one game specifically about the challenges of mapping (Der Kartograph/Cartographers)! In virtual environments, maps have become an integral element of story telling, crossing the line from games into that other huge arena of popular and distracting cartography, maps in literature. (I would like to go on about the place of maps in modern gaming, except that I’m not a gamer and I really know nothing about the topic!)

For all the ways in which maps have been made to create entertainment and to distract us from the rigors of real life in the capitalist, industrial world—even as these popular maps are themselves made possible by the modern economic system—such mapping remains a small part of the myriads of maps that are made and used in modern societies. And, as I hope that I have shown, much of that mapping has the power to distract and divert. The profusion of images of early maps online can provide map-aficionados with many hours of fun!

It is traditional, in some circles of geographers, to end every talk with a sunset. I’ll follow suit, after the obligatory references, below.

Matthew Edney

November 2020

Works Mentioned and Relevant Resources (other than The History of Cartography)

Beresiner, Yasha. 2010. “A Fine Hand: Cartographic and Map Playing Cards, 1590–1798.” Journal of the International Map Collectors’ Society [IMCoS] 122: 15–23.

Dillon, Diane. 2007. “Consuming Maps.” In Maps: Finding Our Place in the World, edited by James R. Akerman, and Robert W. Karrow, Jr., 289–343. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Doll, John. 1994. “Playing with Cards.” Map Collector 66: 26–27.

Feng, Linda Rui. 2018. “Can Lost Maps Speak? Toward a Cultural History of Map Reading in Medieval China.” Imago Mundi 70, no. 2: 169–82.

Hill, Gillian. 1978. Cartographical Curiosities. London: For the British Library by British Museum Publications.

Hopkins, Judith. 1992. “The 1791 French Cataloging Code and the Origins of the Card Catalog.” Libraries & Culture 27, no. 4: 378–404.

Kentish, Brian. 2008. “John Lenthall and His Playing Card Maps of England and Wales.” MapForum 11: 36–40.

Krajewski, Markus. 2011. Paper Machines: About Cards and Catalogs, 1548–1929. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Nielsen, Holly. 2020. “‘The British Empire Would Gain New Strength from Nursery Floors’: Depictions of Travel and Place in Nineteenth-Century British Board Games.” In Historia Ludens: The Playing Historian, edited by Alexander von Lünen, Katherine J. Lewis, Benjamin Litherland, and Pat Cullum, 20–33. London: Routledge.

Norgate, Martin. 2007. “Cutting Borders: Dissected Maps and the Origins of the Jigsaw Puzzle.” Cartographic Journal 44, no. 4: 342–50.

Ristow, Walter W. 1983. “Maps on Greeting Cards.” Map Collector 25: 2–7.

Seville, Adrian. 2008. “The Geographical Jeux de I’Oie[l’oie?] of Europe.” BELGEO 3–4: 427–43.

Shefrin, Jill. 1999. Neatly Dissected for the Instruction of Young Ladies and Gentlemen in the Knowledge of Geography: John Spilsbury and Early Dissected Puzzles. Los Angeles: Cotton Occasional Press.

Wong, Edlie L. 2007. “Around the World and Across the Board: Nellie Bly and the Geography of Games.” In American Literary Geographies: Spatial Practice and Cultural Production, 1500–1900, edited by Martin Brückner and Hsuan L. Hsu, 296–324. Newark: University of Delaware Press.

Fig. 18. Sunset Limited (Springfield, Mass.: Milton Bradley, 1920). Original: 17 × 27 cm. Osher Map Library and Smith Center for Cartographic Education, University of Southern Maine (Osher Collection). Click image to see in high resolution on the institutional website, and also its game board.