Below, project director Matthew Edney describes what it takes to send Volume Five of The History of Cartography to Press! Find related articles at 2024 Outreach Extras.

Please consider contributing your support to the international effort that is the History of Cartography Project – click “Make A Gift” at right to donate online!

What Does it Mean to Send the Volume Five “Manuscript” to Press?

You have written a book, and it’s been accepted for publication—congratulations! But now what? How do you turn what you have written into an actual book? You have to send your manuscript to the publisher (the press), which will undertake the necessary steps—from careful copyediting of the manuscript to the final book’s international distribution in physical and digital form. Modern digital technologies seem to simplify the process and allow anyone to publish their work. But authors, who are adept at stringing words together in new and exciting ways, are not designers, who can lay out pages so that they can be read effortlessly, nor are they indexers, who create an entirely different framework to guide readers through the book.

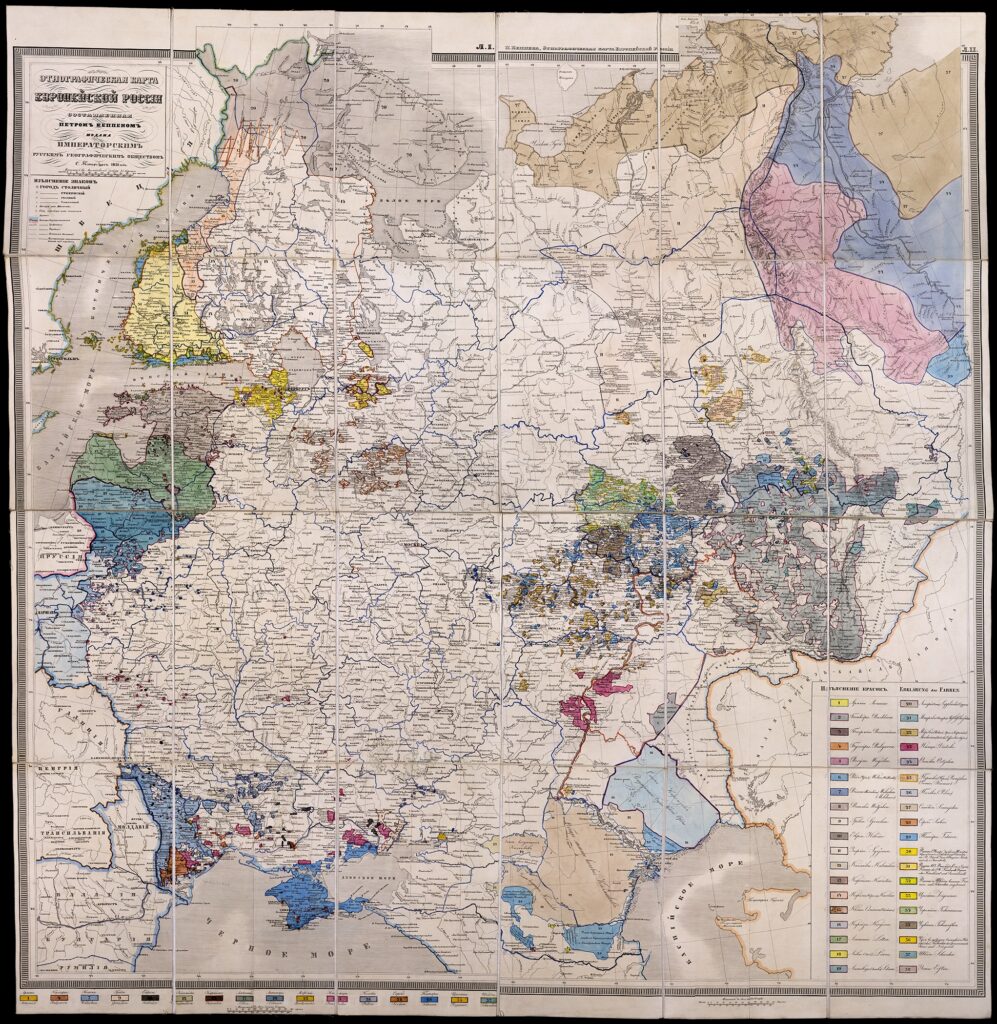

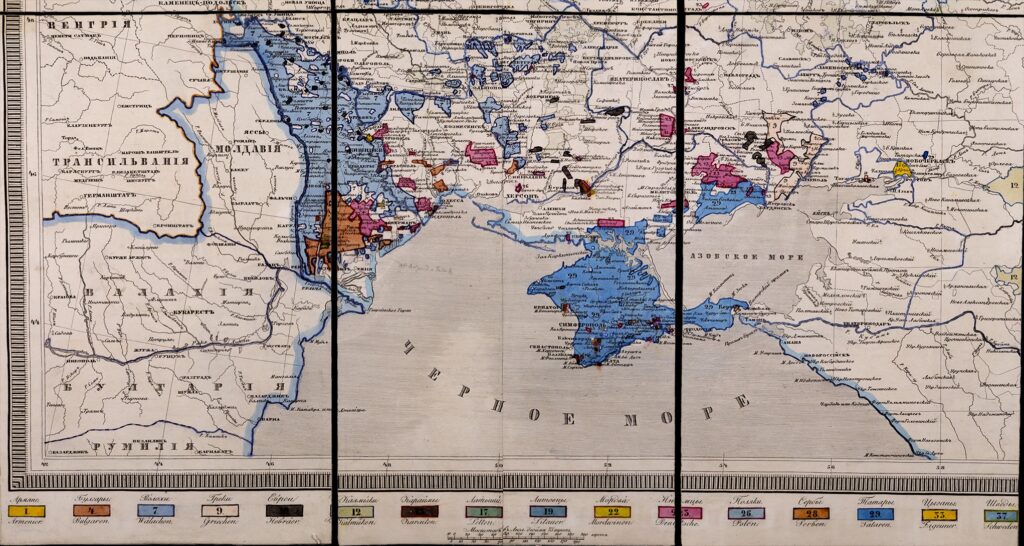

For a book as large and as complex as The History of Cartography, the steps are all that much more complicated and time consuming, requiring extensive professional expertise. Most academic books are considerably more complex than the novels that we commonly read. A novel is almost exclusively words, but academic books often contain images, too, with bibliographical citations and an index at the end. For Cartography in the Nineteenth Century, Volume 5 of The History of Cartography, this means that we must send the University of Chicago Press several different elements. First, there is one very large file folder that holds all the text—over one million words—that will make up most of the final book, from the title page and other front matter; through all the content from A to Z complete with all the citations, tables, and cross-references; to the list of contributors and other back matter (except for the index). Great care is needed to ensure that this folder is correctly assembled from the separate entries, with all the headings properly labeled. Then there are the over one thousand images, numbered in sequence from 1 to 1,054, each a separate high-resolution digital file sized to the final printed page (see figures). A separate file holds all of the captions to the images. Finally, we submit a spreadsheet that guides the Press’s staff through the mass of documentation we prepare demonstrating that we have secured all the permissions needed to reproduce the images.

What Happens after Volume Five is Sent to Press?

The University of Chicago Press has turned every volume of The History of Cartography into physical and electronic books. The process is very complex and requires multiple stages. At each stage, the Press’s work is carefully checked by Project staff. One set of considerations encompasses the design of the books—the specifications of the book trim size; column widths; font type and size, format for each text element; running heads, etc.—and their covers (dust jackets). Fortunately for Volume Five there already exist well-defined templates for both.

The text of the volume is divided by the Press into (usually) six batches for ease of processing. Each batch is carefully copyedited (checking spelling, punctuation, capitalization, and style) to ensure that the text is correct and consistent, a difficult task for a million-word manuscript. Once a batch is copyedited and that copyediting work is reviewed and approved by a History of Cartography editor (which happens with every batch at every stage), the batch is typeset into columns of text only (no captions or illustrations) to produce “galley pages.” In parallel, the images are organized and printed in color at their intended sizes together with their captions; the image files are adjusted until the Press and History of Cartography volume 5 editor are satisfied with the reproduced colors. The designers then integrate the images, captions, and galleys and add page numbers and running heads to create “page proofs” that look just like final printed pages. Project staff review the proofs to ensure that the layout is appropriate to the content, for example, that all the images required for an entry fall within the entry’s page range. In parallel, a professional indexer works with the page proofs to prepare a detailed index; after editorial review the index is itself copyedited and typeset.

With the index complete, the whole work can be sent to the printer to produce the physical book and also can be turned into a file suitable for online access. While all this work is going on, the Press’s marketing team prepares and begins the process of advertising the book. The final step that marks the actual publication is when the printed copies are brought into the Press’s warehouse and prepared for distribution.